Half-t Priors, Conjugacy, and Prior Predictive Distributions

DISCLAIMER: This is a blog post from my graduate school years. The blog is no longer maintained and the material might include typos and errors.

Prior distributions for scale parameters are often hard to choose. While, it is well-known that the inverse-Gamma distribution is the conditional conjugate prior for the variance of a Normal likelihood, the often used $\text{inverse-Gamma}(a,a)$ prior with small values of $a$, might generate some problems in studies with small sample sizes, as pointed out here. Indeed, the paper shows that the posterior is quite sensitive to the choice of $a$ if the number of data points is small; so, it is hardly “uninformative,” which is the whole purpose of using this prior distribution.

The conditional conjugacy of the inverse-Gamma prior makes it attractive in Gibbs sampling schemes, as it leads to a conditional posterior distribution which has a known analytic form. Yet, given its limitations, we might think about other distributions that can be used instead of the inverse-Gamma. Among those, the half-t family has been often recommended. Furthermore, in turns out that, half-t distributions can be formulated as mixtures or products of distributions that are conditionally conjugate as well.

The $\text{half-t}(\nu_0, \eta_0)$ distribution arises naturally from the (generalized) $\text{Student’s t}(\nu_0,\mu_0,\eta_0)$ distribution, where the parameters are, in order, the degrees of freedom, location, and scale parameter. We call it the generalized Student’s t, since the “usual” t-distribution is parameterized by only one parameter, namely $\nu_0$. The half-t distribution can be understood in the same way as the half-Normal distribution. That is, if $X\sim \text{Student’s t}(\nu_0, 0, \eta_0)$, then $\vert X\vert \sim \text{half-t}(\nu_0, \eta_0)$. The density function of the $\text{half-t}(\nu_0,\eta_0)$ is given as

\[p(\sigma) \propto \left[1 + \nu_0^{-1}\left(\frac{\sigma^2}{ \eta_0^2}\right)\right]^{-(\nu_0 + 1)/2}, \quad \nu_0 > 0, \eta_0 > 0,\]for $\sigma > 0$.

The half-t distribution as a scale-mixture of inverse-Gamma distributions

In a paper on variational approximations, Wand and colleagues noted that the half-t distribution can be expressed as the compound of inverse-Gamma distributions (see Result 5 in their paper). That is,

\[\text{If } \sigma^2\,\vert\, \omega \sim \text{inverse-Gamma}\left(\frac{\nu_0}{2}, \frac{\nu_0}{\omega}\right)\text{ and } \omega \sim \text{inverse-Gamma}\left(\frac{1}{2}, \frac{1}{\eta_0^2}\right),\]then $\sigma \sim \text{half-t}(\nu_0, \eta_0).$ Notice that it’s the square-root of $\sigma^2$ that has the desired distribution not $\sigma^2$ itself.

According to the authors, this result is “established in the literature, and straightforward to derive” (p. 855.), but I never came across it. So, let’s try to derive it ourselves. First, we consider the distribution of $\sigma^2$:

\[\begin{aligned} p(\sigma^2) &= \int p(\sigma^2, \omega) \text{d} \omega= \int p(\sigma^2\,\vert\, \omega)p(\omega) \text{d} \omega \\ &\propto \int (\nu_0/\omega)^{\nu_0/2}(\sigma^2)^{-\nu_0/2 - 1}e^{-\nu_0\omega^{-1} \sigma^{-2}}\omega^{-1/2-1}e^{- \eta_0^{-2}\omega^{-1}}\text{d} \omega \\ &\propto (\sigma^2)^{-\nu_0/2 - 1}\int\left[(\omega^{-1})^{(\nu_0 + 1)/2+1}e^{-( \eta_0^{-2}+ \nu_0\sigma^{-2})\omega^{-1}}\right]\text{d} \omega \\ &\propto (\sigma^2)^{-1/2}\left(1 + \frac{\sigma^2}{\eta_0^2 \nu_0}\right)^{-(\nu_0 + 1)/2} \\ \end{aligned}\]where the last step follows from the fact that the integrand is just the unnormalized inverse-Gamma density with parameters $(\nu_0 + 1)/2$ and $\eta_0^{-2} + \nu_0\sigma^{-2}$. Notice that this is the F-distribution with degrees of freedom parameters $\text{df}_1 = 1$ and $\text{df}_2 = \nu_0$ if we set $\eta_0=1$.

Now, this is the density of $\sigma^2$ but what we are interested in is the density of $\sigma$. As the square-root function is bijective and its inverse is continuously differentiable and non-zero on $\mathbb R_+$, we might use the change of variable formula to obtain

\[\begin{aligned} p_\sigma(\sigma) &= p_{\sigma^2}(\sigma^2)\left\vert \frac{d\sigma^2}{d\sigma}\right\vert \\ &\propto \left[1 + \nu_0^{-1}\left(\frac{\sigma^2}{\eta_0^2}\right)\right]^{-(\nu_0 + 1)/2} \end{aligned}\]for $\sigma > 0$, which we recognize as the kernel of a half-t distribution with degrees of freedom parameter $\nu_0$ and scale parameter $\eta_0$.

half-t distribution as the product of a Normal and the square-root of an inveres-Gamma distributed variable

A better-known way to get at the half-t distributions is the following. Suppose $Z\sim \text{Normal}(0,1)$ and $X \sim \text{Chi-squared}(\nu_0)$ are independent. Then $Z/\sqrt{X/\nu_0} \sim \text{Student’s t}(\nu_0)$, as we might recall from the so-called t-test to compare two means. But the $\text{Chi-squared}(\nu_0)$ distribution is, by definition, a $\text{Gamma}(\nu_0/2, 1/2)$ distribution and if $W \sim \text{Gamma}(a,b)$ and $c$ is a positive constant, then $cW \sim \text{Gamma}(a, b/c)$. Thus, $X/\nu_0 \sim \text{Gamma}(\nu_0/2, \nu_0/2)$ and $1/(X/\nu_0) \sim \text{inverse-Gamma}(\nu_0/2, \nu_0/2)$. It follows that we can simulate from a $\text{Student’s t}(\nu_0)$ distribution by first drawing $Z \sim \text{Normal}(0,1)$, then independently drawing, $Y \sim \text{inverse-Gamma}(\nu_0/2, \nu_0/2)$, and calculating $Z\sqrt{Y}$. Further, if $T \sim \text{Student’s t}(\nu_0)$ then $W = \mu_0 + \eta_0T$ is distributed as (generalized) $\text{Student’s t}(\nu_0, \mu_0, \eta_0)$, which suggests that we can obtain random draws from the $\text{half-t}(\nu_0,\eta_0)$ distribution by the following steps:

- Draw $Z\sim \text{Normal}(0, \eta_0)$ (or draw $\tilde Z\sim \text{Normal}(0,1)$ and set $Z = \eta_0 \tilde Z$)

- Independently, draw $Y\sim \text{Inverse-Gamma}(\nu_0/2, \nu_0/2)$.

- Set $T = \vert Z\sqrt{Y}\vert $.

then $T \sim \text{half-t}(\nu_0, \eta_0)$.

Simulating half-t variates

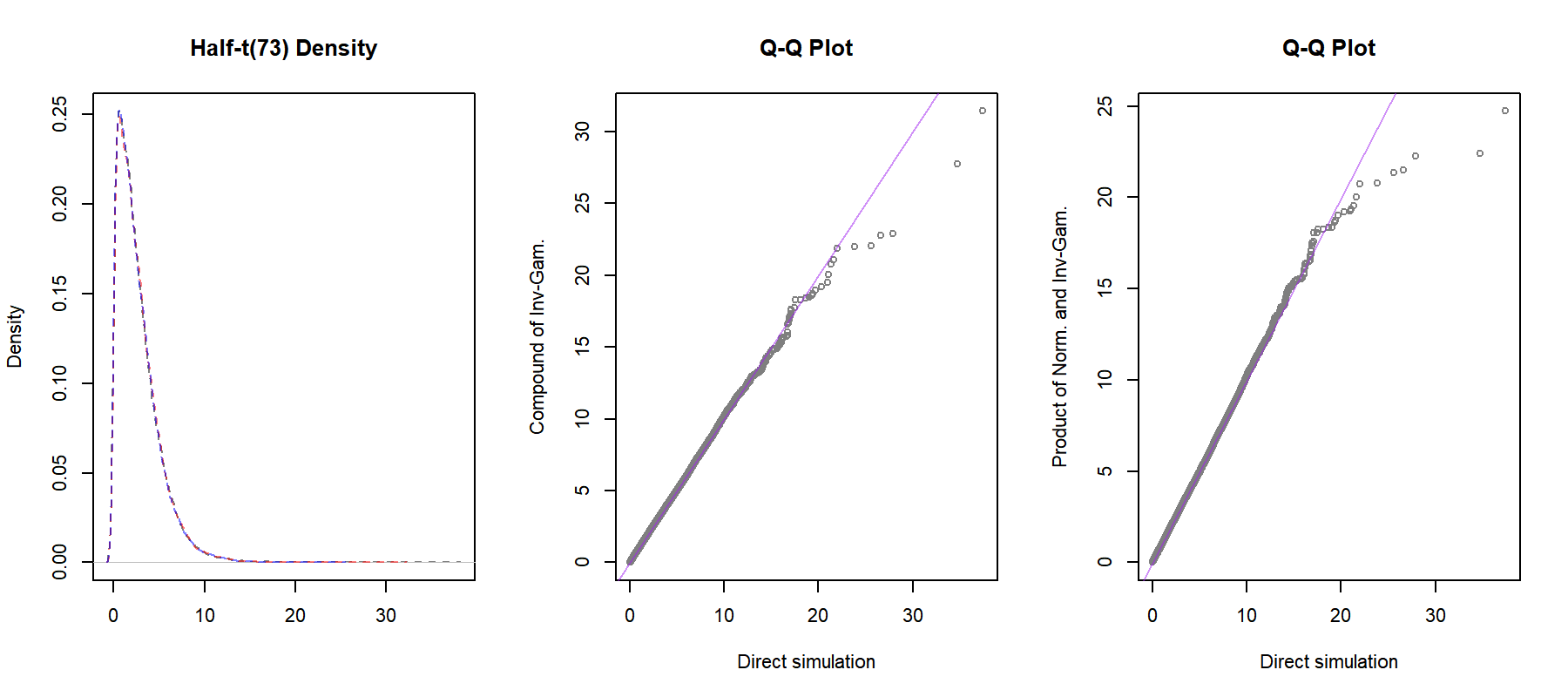

We might validate this result also via simulation:

# seed, parameters, and colors

set.seed(123)

n.sim = 30000

nu0 = 7

eta0 = 3

purple.5 = scales::alpha("purple", 0.5)

blue.5 = scales::alpha("blue", 0.5)

red.5 = scales::alpha("red", 0.5)

black.5 = scales::alpha("black", 0.5)

# simulate n samples using R's rt function

sim.1 = abs(eta0 * rt(n.sim, df = nu0))

# simulate n samples using inverse gamma distributions

omega = 1 / rgamma(n.sim, shape = 0.5, rate = 1 / eta0^2)

sim.2 = sqrt(1 / rgamma(n.sim, shape = 0.5 * nu0, rate = nu0 / omega))

# simulate using product of normal and inverse-gamma

z = rnorm(n.sim, 0.0, eta0)

w = 1 / rgamma(n.sim, 0.5 * nu0, 0.5 * nu0)

sim.3 = abs(z * sqrt(w))

# plot results

par(mfrow = c(1,3))

plot(density(sim.1),

col = black.5,

lty = 2,

main = paste0("Half-t(", nu0, eta0,") Density"),

xlab = "", ylab = "Density")

lines(density(sim.2), col = red.5, lty = 2)

lines(density(sim.3), col = blue.5, lty = 2)

qqplot(sim.1, sim.2,

col = "grey50",

main = "Q-Q Plot",

xlab = "Direct simulation",

ylab = "Compound of Inv-Gam.",

cex = .8)

abline(a = 0, b = 1, col = purple.5)

qqplot(sim.1, sim.3,

col = "grey50",

main = "Q-Q Plot",

xlab = "Direct simulation",

ylab = "Product of Norm. and Inv-Gam.",

cex = .8)

abline(a = 0, b = 1, col = purple.5)

The distributions seem to agree, although the results in the tails are quite unstable. Before we look into conditional conjugacy, notice that the half-t prior has as special cases the half-Normal distribution as $\nu_0 \rightarrow \infty$ and the half-Cauchy distribution when $\nu_0 = 1$, both with scale parameter $\eta_0$. Also, with $\nu_0 = -1$ it reduces to the improper uniform prior $p(\sigma) \propto 1$.

Conditional conjugacy

So far so good. Next, let us look at what happens if we use this prior on the standard deviation parameter in the following simple hierarchical model:

\[\begin{aligned} y_{ij} &\sim \text{Normal}(\theta + \mu_i, 1) \\ \mu_i &\sim \text{Normal}(0, \sigma^2) \end{aligned}\]where $i=1,2,…,n$ and $j=1,2,…,m$ and where we assign the priors

\[\begin{aligned} \theta &\sim \text{Normal}(0, 1) \\ \sigma &\sim \text{half-t}(\nu_0, \eta_0) \end{aligned}\]The posterior is proportional to

\[\begin{aligned} p(\theta, \boldsymbol\mu, \sigma^2\,\vert\, \mathbf y)&\propto p(\mathbf y\,\vert\, \theta, \boldsymbol\mu)p(\boldsymbol\mu\,\vert\, \sigma^2)p(\theta)p(\sigma^2) \end{aligned}\]Next, we use the scale-mixture representation of the half-t distribution and sample $(\sigma^2, \omega) \sim p(\sigma^2, \omega) = p(\sigma^2\,\vert\, \omega)p(\omega)$ and keep only the values of $\sigma^2$, which will be samples from the marginal distribution of $\sigma^2$. The joint prior of $(\sigma^2, \omega)$ is given as

\[\begin{aligned} p(\sigma^2, \omega) &= p(\sigma^2\,\vert\, \omega)p(\omega) \\ &\propto (\nu_0/\omega)^{\nu_0/2}(\sigma^2)^{-\nu_0/2 - 1}e^{-\nu_0\omega^{-1} \sigma^{-2}}\omega^{-1/2-1}e^{- \eta_0^{-2}\omega^{-1}}. \end{aligned}\]and the joint posterior, including $\omega$, is thus

\[\begin{aligned} p(\theta, \boldsymbol\mu, \sigma^2, \omega \,\vert\, \mathbf y)&\propto \prod_{i=1}^n\prod_{j=1}^m \exp\left(-\frac{[y_{ij} - (\theta + \mu_i)]^2}{2}\right) \\ &\quad \times \prod_{i=1}^n \sigma^{-1} \exp\left(-\frac{\mu_i^2}{2\sigma^2}\right) \\ &\quad \times e^{-\theta^2/2}\\ &\quad \times (\sigma^2)^{-\nu_0/2 - 1}\omega^{-(\nu_0 + 1)/2-1}\exp\Big[-\nu_0\omega^{-1} \sigma^{-2} - \eta_0^{-2}\omega^{-1}\Big] \end{aligned}\]The conditionals of $\omega$ and $\sigma$ are, respectively,

\[\begin{aligned} p(\omega\,\vert\, ...) \propto \omega^{-(\nu_0 + 1)/2-1} \exp\left[-\left(\frac{\nu_0}{\sigma^2} + \frac{1}{\eta_0^2}\right)\omega^{-1}\right] \\ \propto \text{Inverse-Gamma}\left(\frac{\nu_0 + 1}{2}, \nu_0\sigma^{-2} + \eta_0^{-2}\right) \end{aligned}\]and

\[\begin{aligned} p(\sigma^2\,\vert\, ...)&\propto (\sigma^2)^{-n/2}\exp\left(- \frac{\sigma^{-2}}{2}\sum_{i=1}^n \mu_i^2\right)(\sigma^2)^{-\nu_0/2 - 1}\exp\left[-\left(\frac{\nu_0}{\omega}\right)\sigma^{-2}\right] \\ &\propto \text{Inverse-Gamma}\left(\frac{n + \nu_0}{2}, \frac{1}{2}\sum_{i=1}^n \mu_i^2 + \frac{\nu_0}{\omega}\right), \end{aligned}\]which both belong to the same family as their (conditional) priors.

For completeness, let us also derive the conditionals of the rest of the parameters:

\[\begin{aligned} p(\theta\,\vert\, ...) &\propto \exp\left(-\frac{(mn + 1) \theta^2 - 2\theta\sum_{i,j}( y_{ij} - \mu_i) }{2}\right) \\ &\propto \text{Normal}\left(\frac{\sum_{i=1}^n \sum_{j=1}^m y_{ij} - m \sum_{i=1}^n\mu_i}{mn + 1}, \frac{1}{(mn + 1)^2}\right) \\ p(\mu_i\,\vert\, ...) &\propto \exp\left( \frac{ (m + \sigma^{-2})\mu_i^2 -2\mu_i(\sum_jy_{ij} - m\theta)}{2}\right) \\ &\propto \text{Normal}\left(\frac{\sum_{j=1}^m y_{ij} - m\theta}{m + \sigma^{-2}}, \frac{1}{(m + \sigma^{-2})}\right). \end{aligned}\]Parameter expansion in hierarchical models

The half-t distribution also naturally arises when using “parameter expansion” that is sometimes used to speed up the convergence of Gibbs samplers. We might expressed the parameter-expanded model as

\[\begin{aligned} y_{ij} &\sim \text{Normal}(\theta + \xi_\psi\psi_i, 1) \\ \psi_i &\sim \text{Normal}(0, \varphi^2) \end{aligned}\]where we assign the priors

\[\begin{aligned} \theta &\sim \text{Normal}(0, 1) \\ \varphi^2 &\sim \text{Inverse-Gamma}(\nu_0/2, \nu_0/2) \\ \xi_\psi &\sim \text{Normal}(0, \eta_0^2). \end{aligned}\]Notice that the parameters of our first model can be expressed as

\[\begin{aligned} \mu_i &= \xi_\psi \psi_i \\ \sigma &= \vert \xi_\psi\vert \varphi. \end{aligned}\]Thus, $\sigma$ is modeled as the absolute value of a $\text{Normal}(0,\eta_0^2)$ variable multiplied by a $\text{Inverse-Gamma}(\nu_0/2, \nu_0/2)$ variable, which induces a $\sigma \sim \text{half-t}(\nu_0, \eta_0)$ prior on the hierarchical standard deviation parameter.

For the parameter-expanded model, we have

\[p(\theta, \boldsymbol\psi, \xi_\psi, \varphi^2\,\vert\, \mathbf y) \propto p(\theta)p(\xi_\psi)p(\varphi^2)\prod_{i=1}^np(\mathbf y_i\,\vert\, \theta, \xi_\psi, \psi_i)p(\psi_i\,\vert\, \varphi^2)\]showing that $\xi_\psi$ and $\varphi^2$ are conditionally independent. The full conditionals are given as

\[\begin{aligned} p(\varphi^2\,\vert\, ...) &\propto (\varphi^2)^{-\nu_0/2 - 1}e^{-\nu_0/(2\varphi^2)}(\varphi^2)^{-n/2}\prod_{i=1}^n \exp\left[-\frac{\psi_i^2}{2\varphi^2}\right] \\ &\propto \text{Inverse-Gamma}\left(\frac{n + \nu_0}{2}, \frac{\sum_{i=1}^n \psi_i^2 + \nu_0}{2}\right)\\ p(\psi_i\,\vert\, ...) &\propto \exp\left[-\frac{\sum_{i}\psi_i^2}{2\varphi^2}\right]\exp\left[-\frac{\sum_i\sum_j(y_{ij} - \theta - \xi_\psi\psi_i)^2}{2}\right] \\ &\propto \text{Normal}\left(\bar m_\psi, s_\psi\right) \\ p(\xi_\psi\,\vert\, ...) &\propto e^{-\xi_\psi^2/(2\eta_0^2)}\exp\left[-\frac{\sum_i\sum_j(y_{ij} - \theta - \xi_\psi\psi_i)^2}{2}\right] \\ &\propto\text{Normal}(\bar m_\xi, s_\xi^2) \\ p(\theta\,\vert\, ...) &\propto e^{-\theta^2/2}\exp\left[-\frac{\sum_i\sum_j(y_{ij} - \theta - \xi_\psi\psi_i)^2}{2}\right] \\ &\propto \text{Normal}(\bar m_\theta, s_\theta^2) \end{aligned}\]where

\[\begin{aligned} s_\psi^2 = (\xi_\psi^2m + 1)^{-1}\quad&\text{and}\quad \bar m_\psi = s_\psi^2\left[\sum_{j=1}^m y_{ij} - m\theta\right] \\ s_\xi^2 = \left[m\sum_{i=1}^n \psi_i^2 + \eta_0^{-2}\right]^{-1}\quad&\text{and}\quad\bar m_\xi = s_\xi^2\left[\sum_{i=1}^n\sum_{j=1}^m \psi_iy_{ij} - m \theta \sum_{i=1}^n \psi_i\right] \\ s_\theta^2 = (mn + 1)^{-1}\quad&\text{and}\quad\bar m_\theta = s_\theta^2\left[\sum_{i=1}^n\sum_{j=1}^m y_{ij} - m\xi_\psi\sum_{i=1}^n \psi_i\right] \end{aligned}\]Thus, all priors of the parameter-expanded model are conditional conjugates, which makes sampling from the conditionals simple.

Prior predictive distribution

As the post has become already quite long, let us postpone the implementation of the Gibbs sampler and rather look at what a half-t prior would imply with respect to our beliefs regarding the data. First, we generate a dataset from the hierarchical model (without parameter expansion):

# set new seed (just in case...)

set.seed(1984)

# "true" parameters

theta.star = 0.5

sigma.star = 1.25

# generate data

n = 500

m = 10

mu.star = rnorm(n, 0.0, sigma.star)

y = t(sapply(1L:n, function(w) rnorm(m, theta.star + mu.star[w], 1.0)))Next, we examine what datasets would be consistent with our prior beliefs regarding the parameters. This can be done by examining the prior predictive distribution:

\[p(\tilde y) = \int (\tilde y, \theta) \text{d}\theta = \int p(\tilde y\,\vert\,\theta)p(\theta)\text{d}\theta.\]The prior predictive distribution can be thought of as the distribution of data that are implied by (or consistent with) our priors. There are two thing that might be notice about the equation above. First, it is a distribution of the data, $\tilde y$, not the parameters. Second, in principle, it is a distribution of the data that are not yet observed (hence the tilde above $y$). Everything that enters the equation above is just the likelihood (or sampling distribution), $p(\tilde y\,\vert\, \theta)$, and our prior distribution $p(\theta)$, and we ask “given our prior and the assumed data-generating process, what kind of data might we observe?”

While evaluating the integral in the expression above might be complicated, it is easy to simulate draws from the prior predictive distribution. This procedure follows exactly that same steps as generating draws from the posterior predictive distribution (which was examined here) except that we are using draws from $p(\theta)$ (the prior) and not $p(\theta\,\vert\, y)$ (the posterior). Further, generating draws from both the posterior predictive and the prior predictive distribution follows basically the same steps as those that were used to simulate the data, except that we simulate one dataset for each drawn $\theta \sim p(\theta)$ instead of just one dataset using a single fixed “true” value of $\theta$.

So, why would we want to simulate from the prior predictive distribution? The benefits we gain are also quite stratighforward to understand: namely we see how strong or weak our priors actually are. One of the very strength of Bayesian analysis is the incorporation of prior information, by which we can draw our estimates towards more reasonable values and away from unrealistic parameter values (such as a logistic regression coefficient of, say, $50$.) By assigning less probability on unreasonable parameter values with the prior distribution, we can gain in precision—i.e, stronger priors will reduce the expected posterior variance. Of course, with large data and smoothly varying prior distributions, the information contained in the data will always dominate. Yet, in small and noisy datasets, a good prior might be very important.

Now, let’s see simulating from the prior predictive distribution works. We set the number of simulation draws to $1,000$ and code up a function that draws datasets from the prior predictive distribution as follows:

# no of draws from ppd

n.sim = 1000

# function to draw from ppd

gen.ppd = function(n.sim, nu0, eta0) {

# sample theta

p.theta = rnorm(n.sim, 0.0, 1.0)

# sample sigma

p.sigma = abs(eta0 * rt(n.sim, nu0))

# sample mu

p.mu = t(replicate(n, rnorm(n.sim, 0.0, p.sigma)))

# sample y

p.y = lapply(1:n.sim, function(w) {

t(sapply(1:n, function(v) {

rnorm(m, p.theta[w] + p.mu[v, w], 1.0)

}))

})

return(p.y)

}As we are concerned here with the parameter $\sigma$—the standard deviation of the group-means—we might look how much the average outcome varies across the groups, i.e., the $i$ units. That is, for all $i = 1,2,…,n$ we calculate $\bar y_i = m^{-1}\sum_{j=1}^m y_{ij}$ and examine the distribution of $\text{sd}(\bar y_i) = \sqrt{(n-1)^{-1} \sum_{i=1}^n(\bar y_i - \bar y)^2}$, where $\bar y = (nm)^{-1}\sum_{i=1}^n\sum_{j=1}^m y_{ij}$.

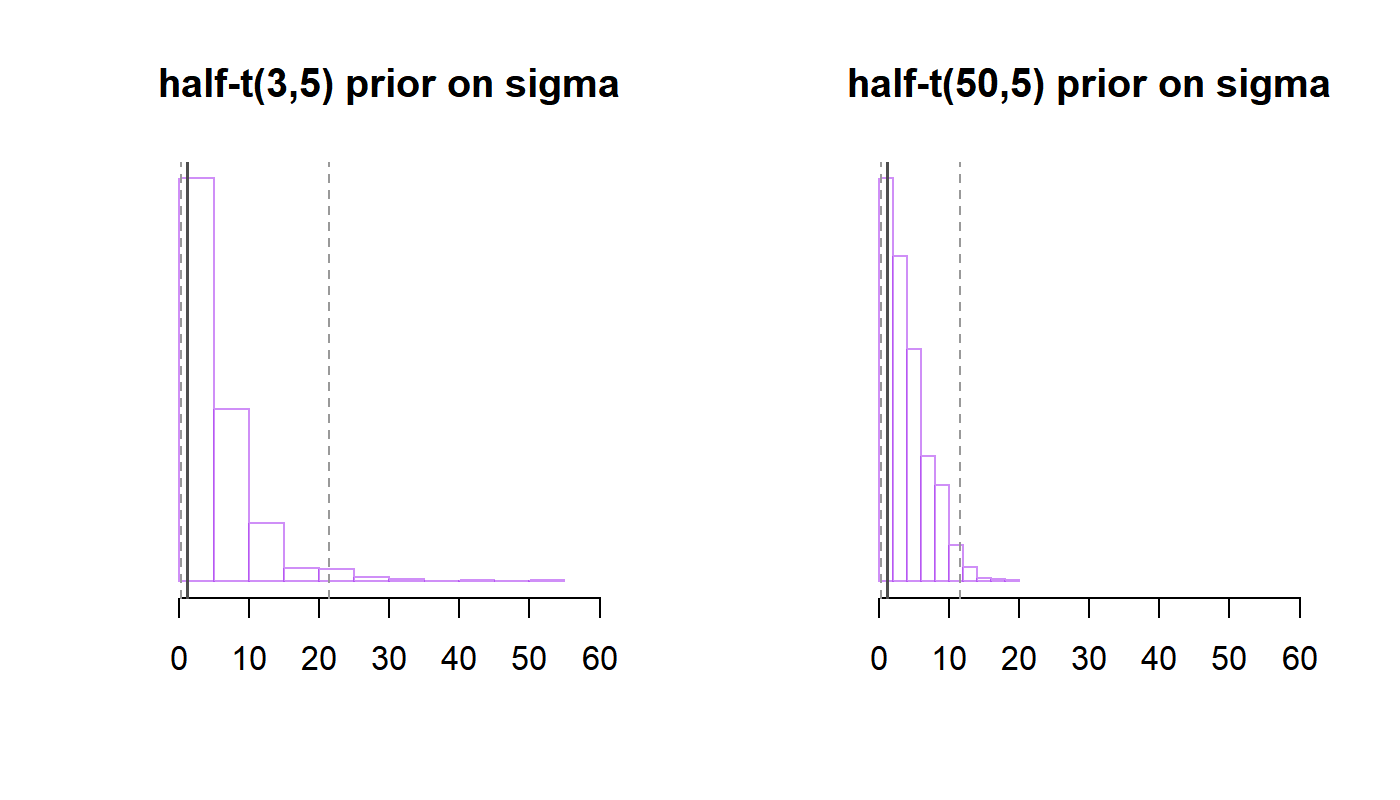

We might compare two priors: the $\text{half-t}(3,5)$ and the $\text{half-t}(50, 5)$, the latter of which will be quite close to the $\text{half-Normal}(5)$ distribution. This is done by drawing n.sim datasets from the respective prior predictive distribution, calculate the group-level standard deviation across the simulated datasets, and plotting the distribution or calculating some statistics of interest.

# simulate data from the prior predictive distribution

# with half-t(3,5) prior on sigma

nu1 = 3

eta1 = 5

pp.dat.1 = gen.ppd(n.sim, nu1, eta1)

# same with half-t(50,5)

nu2 = 50

eta2 = 5

pp.dat.2 = gen.ppd(n.sim, nu2, eta2)

# calculate standard deviation across i units

pp.sd.i.1 = sapply(pp.dat.1, function(w) {

ybar = rowMeans(w)

sd(ybar)

})

pp.sd.i.2 = sapply(pp.dat.2, function(w) {

ybar = rowMeans(w)

sd(ybar)

})

# plot results, half-t(3,5)

par(mfrow = c(1,2))

hist(pp.sd.i.1,

col = "white",

xlim = c(0,60),

freq = F,

border = purple.5,

yaxt = "n",

xlab = "",

ylab = "",

main = paste0(

"half-t(", nu1, ",", eta1, ") prior on sigma")

)

# sd(ybar_i)

abline(v = sd(rowMeans(y)), col = "grey30", lwd = 1.5)

# plot 95% interval

q.95 = quantile(pp.sd.i.1, c(.025, .975))

abline(v = q.95, col = "grey60", lty = 2)

# plot results, half-t(3,10)

hist(pp.sd.i.2,

col = "white",

xlim = c(0,60),

freq = F,

border = purple.5,

yaxt = "n",

xlab = "",

ylab = "",

main = paste0(

"half-t(", nu2, ",", eta2, ") prior on sigma")

)

# sd(ybar_i)

abline(v = sd(rowMeans(y)), col = "grey30", lwd = 1.5)

# plot 95% interval

q.95 = quantile(pp.sd.i.2, c(.025, .975))

abline(v = q.95, col = "grey60", lty = 2) We see that the $\sigma \sim \text{half-t}(3,5)$ prior is consistent with values of $\text{sd}(\bar y_i)$ as large as 20, or even larger values, while the $\text{half-t}(50,5)$ prior puts more probability on smaller values of $\sigma$. Whether these priors are “reasonable” will depend on the specific application. Had we strong contextual knowledge that that $\sigma$ is quite small, say $\sigma < 2$, the $\text{half-t}(3,5)$ prior would be unnecessarily wide. Similarly, if you analyze a typical survey and find a logistic regression coefficient to be estimated $\beta \approx 50$ (assuming that the variance of the corresponding predictor is not too small), you’d check your code for errors, how missing values were coded, and so on, rather than taking this point estimate as the truth, because you know that this estimate is simply too large (and you’ll probably find that something was coded incorrectly). Thus, a prior that puts significant weight on $\beta = 50$, say $\beta \sim \text{Normal}(0, 50^2)$, might be considered to be unrealistically wide. To reiterate, in large datasets, quite any prior (even improper ones) will lead to similar conclusions (given that the posterior is proper, of course); but for smaller datasets or parameters for which the data contains only limited information, the choice of the prior can be quite important. Plotting out the implications of the prior via the prior predictive distribution can be very helpful in these situations.

We see that the $\sigma \sim \text{half-t}(3,5)$ prior is consistent with values of $\text{sd}(\bar y_i)$ as large as 20, or even larger values, while the $\text{half-t}(50,5)$ prior puts more probability on smaller values of $\sigma$. Whether these priors are “reasonable” will depend on the specific application. Had we strong contextual knowledge that that $\sigma$ is quite small, say $\sigma < 2$, the $\text{half-t}(3,5)$ prior would be unnecessarily wide. Similarly, if you analyze a typical survey and find a logistic regression coefficient to be estimated $\beta \approx 50$ (assuming that the variance of the corresponding predictor is not too small), you’d check your code for errors, how missing values were coded, and so on, rather than taking this point estimate as the truth, because you know that this estimate is simply too large (and you’ll probably find that something was coded incorrectly). Thus, a prior that puts significant weight on $\beta = 50$, say $\beta \sim \text{Normal}(0, 50^2)$, might be considered to be unrealistically wide. To reiterate, in large datasets, quite any prior (even improper ones) will lead to similar conclusions (given that the posterior is proper, of course); but for smaller datasets or parameters for which the data contains only limited information, the choice of the prior can be quite important. Plotting out the implications of the prior via the prior predictive distribution can be very helpful in these situations.